Health Promotion in Rural Kenya

Village HopeCore's Fight Against Non-Communicable Diseases

Mary is a 48-year-old mother of 4 and a teacher at primary school X in Mwimbi sub-county, rural Kenya. Four years ago, she was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2 and high blood pressure and was put on oral medication. In addition, she was counseled on diet; low salt intake, low cholesterol intake, sugar-free foods, increased fluid intake, etc. She was also counseled on drug adherence and enrolled in diabetes and hypertension outpatient clinics for 2 weekly follow-ups.

Charity Wanja, a HopeCore Community Health Volunteer, educates a client on Non-Communicable diseases during a home visit

Mary takes her medication as instructed. She restocks her drugs by buying them from a nearby pharmacy. Sometimes, she misses taking her medications when she has no money to buy them or when the pharmacy runs out of their own stock, or when she travels and forgets her drugs at home. She does not attend the outpatient clinics she was enrolled in. She does not regularly monitor her blood glucose levels or her blood pressure as she has no glucometer or blood pressure monitoring machine at home. She only gets her sugars and blood pressure taken when she is ill and visits a health facility or when there is a health outreach activity in the neighborhood. She says a random blood glucose level of 15mmol/l is okay as she is used to levels of more than 20mmol/l.

Mothers receiving education on NCDs at one of HopeCore's Maternal Child Health Clinics

She says she tries to observe the recommended diet while at home but finds a challenge while at school as there is no program for those on a special diet and has no say on how the meals are prepared and so she eats the meals prepared for the rest of the staff.

Recently, Mary has been having blurred vision and has used antibiotic and corticosteroid eye drops purchased from the pharmacy. It is not any getting better but she does not think it is related to her two chronic conditions.

Mary is your typical rural Kenya chronic Non-Communicable Disease (NCD), patient. In the course of my mobile clinic and outreach activities, I have encountered 3 categories of these patients. The first category is those who adhere to medications, know their drugs by name and dosage, attend their enrolled outpatient clinics at least fortnightly and adhere to the strict dietary recommendations.

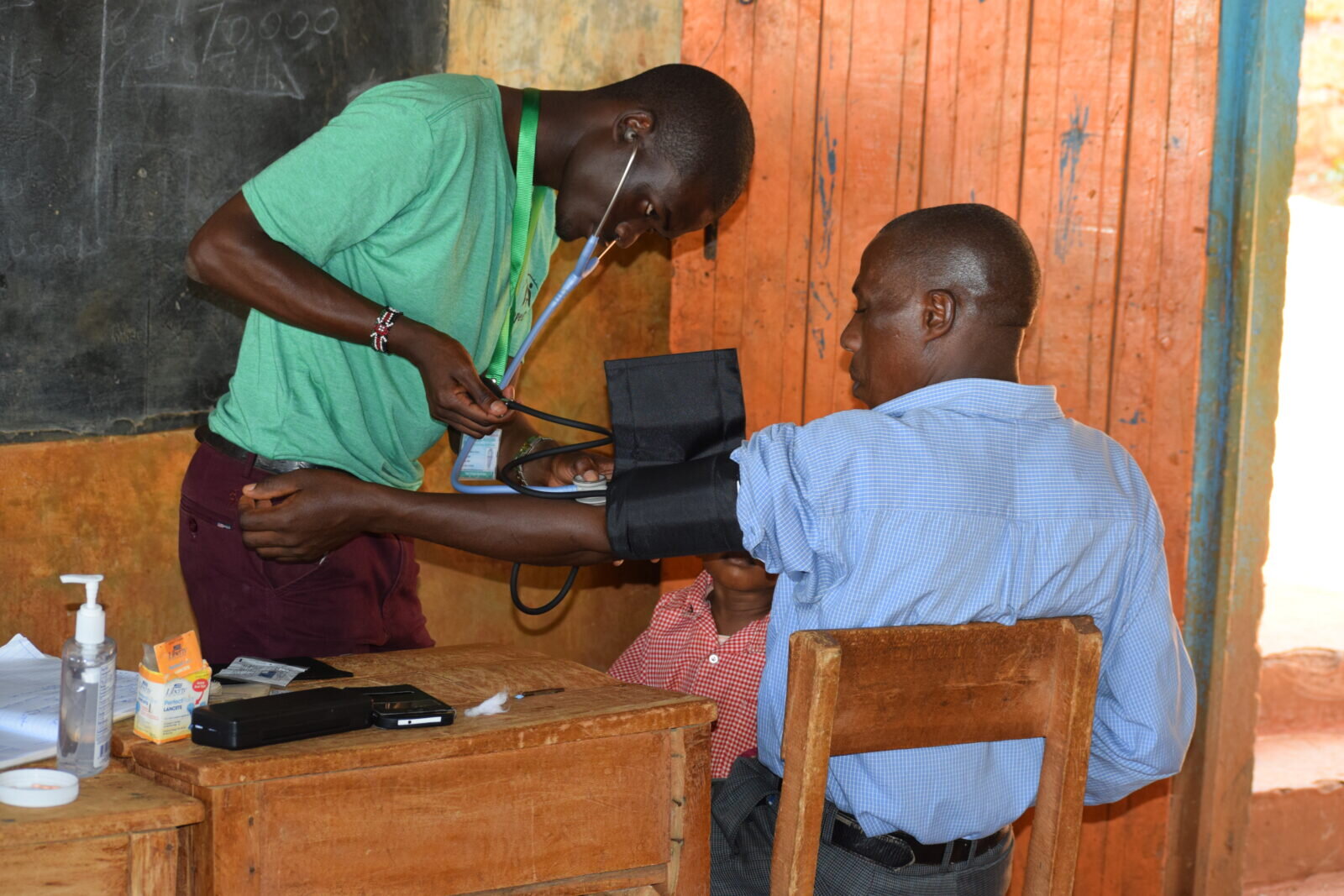

Walter Echesa checks the blood pressure of a client at one of HopeCore free mobile clinics

The second category is where Mary falls; they have some level of formal education and some college diplomas. Some have medical insurance coverage. They take their medications faithfully, refill them from over the counter (claims their outpatient points are too far), occasionally miss the daily doses due to lack of money to buy the drugs, pharmacy drug stock-outs, some are too busy to restock and think missing for a few days does no harm. they sometimes attend their respective outpatient clinics (once a month) for monitoring and check-ups and drug restocking. They partially adhere to a diet, following the recommended diet mostly at home and abandoning it when at the workplace or at a function.

Nicholas screening clients at one of the HopeCore outreach events

Then there is the last category; these clients have little or no formal education, most have no medical insurance cover, and they rarely attend outpatient clinics. They have poor drug adherence and only take medications when they are available. Sometimes they go for months without taking their drugs. They are mostly of low social and economic class. The only money they get goes into buying food. They get their drugs from organizations like HopeCore and get their blood pressure and glucose taken during outreach events, medical camps, and mobile clinics. They do not follow any dietary recommendations. They have the most complications from their conditions.

Villagers lining up out the door to receive free health screenings such as glucose checks, HIV and blood pressure testing at HopeCore free Sunday mobile clinic set up at a local school

NCDs are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality accounting for 63% of all deaths globally. This means that NCDs cause more deaths than all other causes combined (WHO 2015-2020).

According to the Post, 2015 Development Agenda report, about half of all deaths in middle and low-income countries are due to NCDs with about 30% being premature (below 60 yrs). The government of Kenya targets 25% relative reduction in premature mortality from the four main NCDs (cardiovascular, diabetes, cancer, and chronic respiratory diseases) by 2025 (WHO 2015-2020) among other strategies;

Promoting healthy lifestyles by reducing modifiable risk factors such as unhealthy diets, unhealthy use of alcohol, tobacco use

Promoting and strengthening advocacy, communication, and social mobilisation for NCD prevention and control

In line with this, HopeCore has a set of strategies that seeks to address the government agenda by tackling the challenge posed by the last two groups:

Dennis Muchemi takes his time to educate a patient on appropriate blood pressure monitoring and teaches the patient how to use a blood pressure cuff

Our outreach events continue to screen the population for early diagnosis. Plans for cervical cancer and prostate cancer screening are underway. Second, we continue to relentlessly do health promotion through client education on the need for screening, the importance of drug and dietary intake adherence, the need for regular monitoring, and the importance of attending the outpatient clinics and working with the health care provider on any aspects that need evaluating. Our education also includes predisposing factors, complications of the conditions if poorly managed, and when to seek care (signs of a complicating disease).

HopeCore health team setting up a triage station to screen for NCDs at a outreach event

We also continue to identify those with extremely low socioeconomic status, helping follow them up with home visits, phone calls, regular monitoring through our office clinic, restocking of their medications, and timely referral for management of complications and blood works. We are also encouraging them to use our Micro Enterprise platform, a poverty eradication program, to emancipate themselves from poverty.

We also continue to empower community health volunteers through training to do door-to-door sensitization and education. The CHVs are also integral in identifying defaulter cases for management.

HopeCore emphasizes that physical activity is one of the major ways to prevent NCDs. Above, HopeCore staff engage in physical activity and practice what the preach! Soccer match between the MedTreks and HopeCore ladies soccer team.